Why MDF was coined the asbestos of the nineties and how to protect yourself

Jump To...

Quick answer

MDF dust poses serious respiratory health risks due to formaldehyde-based resins and ultra-fine particles that penetrate deep into your lungs. The UK workplace exposure limit is 3mg/m3, but HSE found 78% of woodworking businesses were non-compliant in 2022/23. To protect yourself:

- Use M-Class extraction as minimum (99.9% dust capture)

- Wear FFP3 respiratory protection for cutting and sanding MDF

- Get face-fit testing for all tight-fitting masks

- Ensure LEV systems are tested every 14 months

- Request health surveillance from your employer (legally required)

- Never sweep or blow MDF dust with compressed air

The cancer risk from wood dust has a 20-30 year latency period, meaning exposure today could cause nasal cancer in 2045-2055.

Who is this for

This article is essential reading for:

- Joiners, carpenters, and shopfitters who regularly cut or machine MDF

- Kitchen fitters working with MDF carcasses and components

- General builders doing trim work and interior fit-outs

- Workshop owners responsible for employee health and safety compliance

- Self-employed tradespeople setting up dust control for their own protection

The “asbestos of the nineties” controversy

In September 1997, The Observer published an investigation titled “The deadly secret of DIY’s dream material.” The following month, at the Trades Union Congress annual conference, Roy Lockett, deputy general secretary of BECTU, delivered a speech that made national headlines: “MDF is the asbestos of the Nineties. It’s carcinogenic. It causes lesions. It damages the eyes, the skin, the lungs and the heart.”

The comparison sparked outrage from the Wood Panel Industries Federation, whose director-general dismissed the claims as “ill-founded and unsubstantiated rumours” and insisted MDF “has nothing in common with asbestos.” The Health and Safety Executive then commissioned a formal investigation.

Was the comparison fair?

The “asbestos of the nineties” label was hyperbolic, but the underlying health concerns were real. Unlike asbestos, MDF doesn’t cause mesothelioma or the same type of fibrotic lung disease. However, both wood dust and formaldehyde are now classified as Group 1 carcinogens by the International Agency for Research on Cancer, meaning there’s sufficient evidence they cause cancer in humans.

The comparison did serve a purpose: it drew attention to a genuine occupational health risk that many workers were underestimating. Nearly three decades later, HSE statistics show that protection remains inadequate across the industry.

The High Wycombe precedent

The MDF controversy wasn’t the UK’s first wood dust health crisis. In the 1960s, medical researchers documented a shocking pattern in the Buckinghamshire furniture industry centred in High Wycombe: skilled furniture makers exposed to hardwood dust had a cumulative lifetime risk of at least 1 in 120 for developing nasal adenocarcinoma, approximately 100 times higher than the general population.

In 1968, Parliament formally discussed the link between nasal cancer and hardwood dust. This historical precedent meant that by 1997, when the MDF debate erupted, the carcinogenic nature of wood dust was already well-established in medical literature.

Understanding the health risks

The double hazard of MDF

MDF presents two distinct hazards that natural timber doesn’t:

Formaldehyde content: MDF is composed of approximately 82% wood fibre, 9% urea-formaldehyde resin glue, 8% water, and 1% paraffin wax. When you cut or sand MDF, you’re not just releasing wood particles; you’re releasing ultra-fine wood dust coated with formaldehyde resin.

Particle size: MDF creates exceptionally fine dust particles. One experienced woodworker on a UK forum described routing circles in MDF: “Most of it ended up in the air, with a thin layer settling on every surface the next day despite having a ceiling-mounted dust extractor.”

These ultra-fine particles bypass your nose’s natural filtering system and penetrate deep into the respiratory system, reaching the alveoli where gas exchange occurs.

Immediate symptoms you might recognise

If you’ve worked with MDF, you’ve probably experienced some of these:

- Eye irritation that lasts for hours after you’ve finished work

- Runny nose and nasal inflammation

- Scratchy throat

- Shortness of breath, coughing, or wheezing

- Skin irritation where dust settles on sweaty skin

One forum user reported: “MR MDF gives me flu-like symptoms if I cut a lot. The dust seems to come off in waves.” Another wrote: “The worst thing with MDF dust is eye irritation. My eyes are sore for hours afterwards.”

These aren’t minor inconveniences. They’re your body’s warning system telling you that harmful substances are penetrating your defences.

Long-term health consequences

The serious health risks develop over years and decades of exposure:

Occupational asthma: Carpenters and joiners are four times more likely to develop asthma compared to other UK workers. Wood dust is marked as a respiratory sensitiser in HSE’s EH40 guidance, meaning it can trigger allergic reactions that worsen over time. Once you develop sensitisation, even tiny amounts of dust can trigger severe reactions.

Chronic respiratory disease: Prolonged exposure can cause chronic bronchitis and hypersensitivity pneumonia, permanently reducing lung function.

Sinonasal cancer: This is the most serious risk. Adenocarcinoma of the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses is rare in the general population but significantly elevated in woodworkers. The critical factor: cancer from wood dust exposure has a latency period of 20-30 years after initial significant exposure.

That means if you’re 30 years old and working with MDF daily without adequate protection, you won’t see the consequences until you’re 50-60. The exposure you accept today could cause cancer when you’re approaching retirement.

Dermatitis: Allergic skin reactions can develop after days or weeks of repeated contact with MDF dust, causing itching, redness, and dry, cracked skin.

Current UK regulations and enforcement

Workplace exposure limits

The current UK workplace exposure limit (WEL) for hardwood dust, which applies to MDF, is 3mg/m3 measured as an 8-hour time-weighted average. For comparison, the EU adopted a stricter limit of 2mg/m3, but the UK has not followed suit post-Brexit.

For mixed hardwood and softwood dusts, the stricter hardwood limit of 3mg/m3 applies to all wood dust in that mixture. There’s also a separate limit for formaldehyde of 2 ppm.

What does 3mg/m3 mean in practice? It’s roughly equivalent to a pinch of dust dispersed in a cubic metre of air. It’s a very small amount, and without proper extraction, you’ll exceed it quickly when cutting or sanding MDF.

COSHH requirements

Under the Control of Substances Hazardous to Health Regulations 2002, employers must:

- Assess the risks from hazardous substances including wood dust

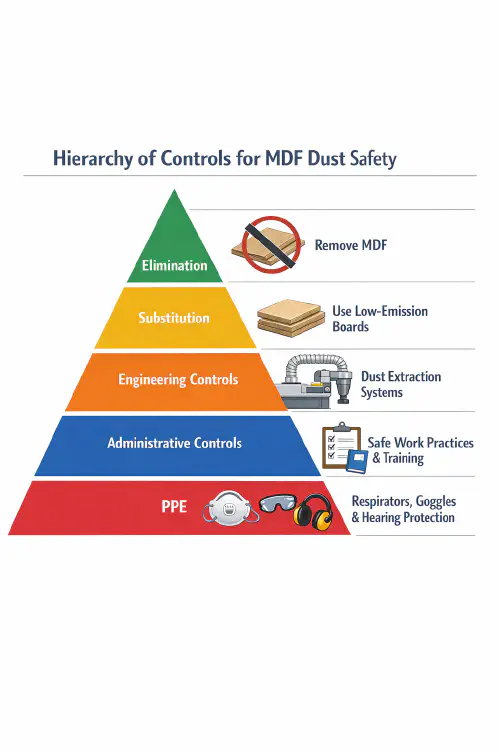

- Implement control measures following the hierarchy of controls

- Provide health surveillance where appropriate (this is mandatory for wood dust exposure)

- Maintain and test Local Exhaust Ventilation systems

- Provide suitable respiratory protective equipment and arrange face-fit testing

- Keep records of assessments, LEV testing, and health surveillance

If you’re self-employed, these duties fall on you. You’re both the employer and the employee, so you need to protect yourself as thoroughly as you would protect someone working for you.

HSE enforcement focus 2025-2026

Wood dust is a key focus for HSE enforcement visits in 2025 and 2026 under the “Dust Kills” campaign. Inspectors are actively targeting construction sites, woodworking workshops, and furniture manufacturers.

The consequences of non-compliance are significant:

- Improvement notices requiring immediate action with specified timelines

- Prohibition notices that stop work entirely until hazards are addressed

- Prosecution with fines ranging from £15,000 to £40,000+ plus legal costs

Recent prosecution examples

Billy Davidson NV Stables Ltd (January 2024): Fined £15,000 plus £4,500 costs after failing to implement improvements despite two previous HSE notices. The LEV system hadn’t been inspected, and dust from a circular table saw wasn’t being controlled.

Nat Pal Limited (May 2025): Fined £40,000 for ongoing failures dating back to 2015. During the inspection, dust was scattered across the floor despite nearly a decade of previous enforcement action.

These aren’t massive corporations. They’re small to medium woodworking businesses, the kind you probably compete with or work for.

Protecting yourself: the hierarchy of controls

COSHH requires you to apply controls in a specific order, starting with the most effective:

The hierarchy of controls for MDF dust safety, from most effective (elimination) to least effective (PPE)

1. Elimination and substitution

Can you avoid creating the dust in the first place?

- Specify pre-cut components where possible

- Consider formaldehyde-free alternatives for projects where client budgets allow:

- MEDITE ECOLOGIQUE: UK-made formaldehyde-free MDF using MDI binder instead of urea-formaldehyde

- MEDITE CLEAR: Zero added formaldehyde, suitable for interior applications

- Evertree: Plant-based binder made in France with emissions 10 times lower than EU E1 standard

These alternatives cost more, but they eliminate the formaldehyde hazard entirely while still leaving the wood dust issue to manage.

2. Engineering controls: Local Exhaust Ventilation

LEV is your primary defence. It captures dust before it reaches your breathing zone.

Legal requirements for LEV systems:

- Must be provided at all woodworking machines

- Tested and inspected by a competent person at least every 14 months

- Log book maintained recording all checks and maintenance

- Airflow indicators fitted so you can see immediately if there’s a problem

M-Class extractors: For MDF and wood dust, M-Class extraction is the minimum legal requirement. These extractors capture at least 99.9% of dust and are certified for medium-risk materials including wood dust, MDF, and concrete.

Standard DIY shop vacuums are not adequate. They might capture visible chips, but they recirculate ultra-fine particles straight back into the air.

Popular M-Class extractors used by UK tradespeople include Festool CTL and CTM models, Nilfisk 33-2M, Vacmaster WD M38 PCF, Trend T32, and DeWalt DWV905M. Expect to pay £200-£800 depending on capacity and features.

On-tool extraction: Connect extraction directly to the dust port on your power tools. Most modern routers, circular saws, sanders, and mitre saws have built-in ports. Use them. A properly connected M-Class extractor on a mitre saw can capture 95%+ of dust at source.

Workshop LEV systems: If you’ve a fixed workshop, consider a ducted LEV system with blast gates at each machine. This is more expensive upfront (£2,000-£10,000 depending on workshop size) but provides better extraction and convenience.

Ceiling-mounted fine dust filters: These don’t replace extraction, but they capture residual fine dust that escapes from tools. They’re particularly useful in workshops where you’re routing or sanding and fine dust inevitably becomes airborne.

3. Safe working practices

Dust cleanup:

- Never sweep MDF dust. Sweeping just resuspends particles into the air where you breathe them in.

- Never use compressed air to blow dust off surfaces or out of machines. This creates dangerous dust clouds.

- Always use an M-Class vacuum or wet cleaning methods.

Work organisation:

- Cut MDF outside or in well-ventilated areas where practical

- Plan cuts to minimise dust generation (plunge cuts create more dust than through cuts)

- Allow dust to settle before removing respiratory protection

- Shower and change clothes after heavy MDF work to avoid bringing dust home

4. Respiratory Protective Equipment

RPE is your last line of defence, not your first. It only works if LEV is inadequate or impractical.

Minimum protection for MDF work:

- Light machining with good LEV: FFP2 (Assigned Protection Factor 10)

- Sanding, routing, heavy cutting: FFP3 (APF 20)

- High dust environments or all-day MDF work: Half-mask respirator with P3 filters (APF 20)

The Assigned Protection Factor tells you how much the mask reduces your exposure. FFP3 with APF 20 means if the ambient dust level is 60mg/m3, you’re actually breathing 3mg/m3 (the workplace limit).

Face-fit testing is mandatory: A mask that doesn’t seal properly offers virtually no protection. Employers must arrange face-fit testing by a competent person for all workers using tight-fitting RPE. This includes the self-employed if you’re working on a site where someone else is the principal contractor.

You must be clean-shaven for masks to seal. A few days’ stubble is enough to break the seal and render the mask ineffective.

Keep records of fit testing. If HSE inspects your site, they’ll ask to see them.

MDF-specific consideration: When cutting MDF at high temperatures with power tools, formaldehyde vapours may be released. If you’re doing prolonged work or notice a chemical smell, consider combined filters (ABP cartridge) that protect against both particles and organic vapours.

5. Health surveillance

This is the bit most employers and self-employed tradespeople don’t know about: health surveillance is legally required for workers exposed to wood dust because it’s a respiratory sensitiser.

What health surveillance involves:

- Baseline assessment ideally before exposure, or within 6 weeks of starting

- Respiratory questionnaire asking about symptoms

- Spirometry (lung function testing) measuring breathing capacity

- Ongoing assessments, usually annually or more frequently for new workers

- Health records maintained for each monitored worker

Who needs it: Everyone who might breathe in wood dust, including those with intermittent exposure. That includes you if you’re cutting MDF even a few times per month.

The scheme should be set up with input from a competent occupational health professional. Your employer should arrange and pay for this. If you’re self-employed, you should arrange your own baseline lung function test and periodic reviews.

Why does this matter? Early detection of respiratory sensitisation means you can take action before permanent damage occurs. If spirometry shows declining lung function, you know your current controls aren’t adequate.

What experienced woodworkers actually do

Forum discussions reveal what protective measures tradespeople actually use in practice:

“I wear a 3M P3 dust mask whenever I’m machining. All my machines are connected to filtered dust extraction, and I’ve upgraded my cyclone extractor to use a 0.3 micron HEPA filter instead of the standard 1 micron.”

“I’ve got a ceiling-mounted fine dust extractor that runs continuously. Even with on-tool extraction, routing MDF fills the air with invisible fine dust.”

“After a full day cutting MDF, I used to get flu-like symptoms the next day. Since upgrading to an M-Class extractor and wearing FFP3 masks, that’s stopped.”

The consistent theme: experienced woodworkers use multiple layers of protection. Extraction AND respiratory protection AND workshop air filtration. Not one or the other.

The bottom line: why this matters now

Over 500 construction workers die from dust exposure annually in the UK. In 2022/23, HSE found 78% of woodworking businesses were failing to protect workers adequately, resulting in 402 enforcement actions.

The cancer risk from wood dust has a 20-30 year latency period. If you’re 35 now and regularly cutting MDF without proper protection, the consequences might appear when you’re 55-65. You won’t connect the nasal cancer diagnosis in 2045 to the kitchen fit you did in 2025, but the link will be there.

This isn’t about being overly cautious. It’s about understanding that MDF dust is a genuine occupational carcinogen with documented evidence of causing cancer, and the UK regulatory system now treats it as such.

The good news: effective protection is achievable and increasingly affordable. A decent M-Class extractor costs less than a quality mitre saw. FFP3 masks cost £2-£5 each. The 14-month LEV inspection costs £100-£300. Health surveillance costs £50-£100 per worker annually.

These aren’t prohibitive costs. They’re the basic cost of doing business safely in an industry where respiratory disease is the leading cause of occupational illness.

Links and references

- HSE - Wood dust guidance - Official HSE page on wood dust risks and controls

- HSE - COSHH and woodworkers - Key messages for the woodworking sector

- HSE - Local exhaust ventilation - LEV requirements and resources

- HSE - EH40/2005 Workplace exposure limits - The definitive UK exposure limits document

- HSE - Respiratory protective equipment - RPE selection and fit testing guidance

- BWF - Wood Dust Focus on LEV - British Woodworking Federation LEV guidance

- Latham Timber - Zero Formaldehyde MDF Panels - Information on formaldehyde-free MDF alternatives

Related TrainAR Academy articles:

- Artex asbestos: how to test, NNLW vs non-licensed, safe drilling and removal steps

- Stop chargebacks on site: photos, signatures and payment flows that protect your jobs

FAQs

Is MDF actually as dangerous as asbestos?

No. The “asbestos of the nineties” label was hyperbolic. MDF doesn’t cause mesothelioma or the type of fibrotic lung disease associated with asbestos. However, both wood dust and formaldehyde in MDF are classified as Group 1 carcinogens by IARC, meaning there’s sufficient evidence they cause cancer in humans. The comparison served to highlight a genuine risk that was being underestimated.

What’s the difference between M-Class and L-Class extractors?

L-Class extractors capture 99% of dust but are only suitable for low-risk materials like plaster dust. M-Class extractors capture 99.9% of dust and are the legal minimum for wood dust, MDF, and concrete. For MDF work, you must use M-Class or higher. Standard DIY shop vacs are typically L-Class at best.

Do I really need face-fit testing for disposable masks?

Yes. The HSE is clear that all tight-fitting respiratory protective equipment requires face-fit testing, including disposable FFP2 and FFP3 masks. A mask that doesn’t seal properly provides virtually no protection. Testing takes 10-15 minutes and must be done by a competent person. Records must be kept.

I’m self-employed. Do these rules apply to me?

Yes. Self-employed workers have the same health and safety duties as employers. You must assess risks, implement controls, and protect yourself as thoroughly as you would protect an employee. If you work on a site with a principal contractor, they may arrange health surveillance and fit testing, but you’re responsible for your own extraction equipment and RPE.

How often do I need to replace FFP3 masks?

Disposable FFP3 masks should be replaced when breathing becomes difficult, when they’re visibly damaged or contaminated, or after extended use (typically 4-8 hours of actual work time depending on dust levels). Reusable half-mask respirators have replaceable P3 filters that should be changed when breathing resistance increases or according to manufacturer guidance, usually every 1-3 months for regular users.

Can I just use a dust mask instead of buying expensive extraction equipment?

No. COSHH requires you to control dust at source using engineering controls (extraction) as the primary method. RPE is only acceptable as a last resort when extraction is inadequate or impractical. Relying on masks alone means you’re breaching COSHH regulations and putting yourself at serious risk. HSE inspectors will issue enforcement notices if they find you’re using RPE without adequate extraction.

What should I do if I’m already experiencing respiratory symptoms?

See your GP immediately and tell them about your occupational exposure to wood dust and MDF. Early intervention is important for conditions like occupational asthma. If you’re employed, inform your employer so they can review controls and arrange health surveillance. If symptoms are work-related, they should improve when you’re away from work (weekends, holidays). This pattern is a warning sign that current protection is inadequate.

Are there MDF alternatives without formaldehyde?

Yes. MEDITE ECOLOGIQUE (UK-made), MEDITE CLEAR, and Evertree all use alternative binders instead of urea-formaldehyde resin. These eliminate the formaldehyde hazard but you still need to control wood dust exposure. They cost more than standard MDF but may be worth specifying for projects where budgets allow, particularly for healthcare, education, or residential applications where indoor air quality matters.

Ready to Transform Your Business?

Turn every engineer into your best engineer and solve recruitment bottlenecks

Join the TrainAR Waitlist